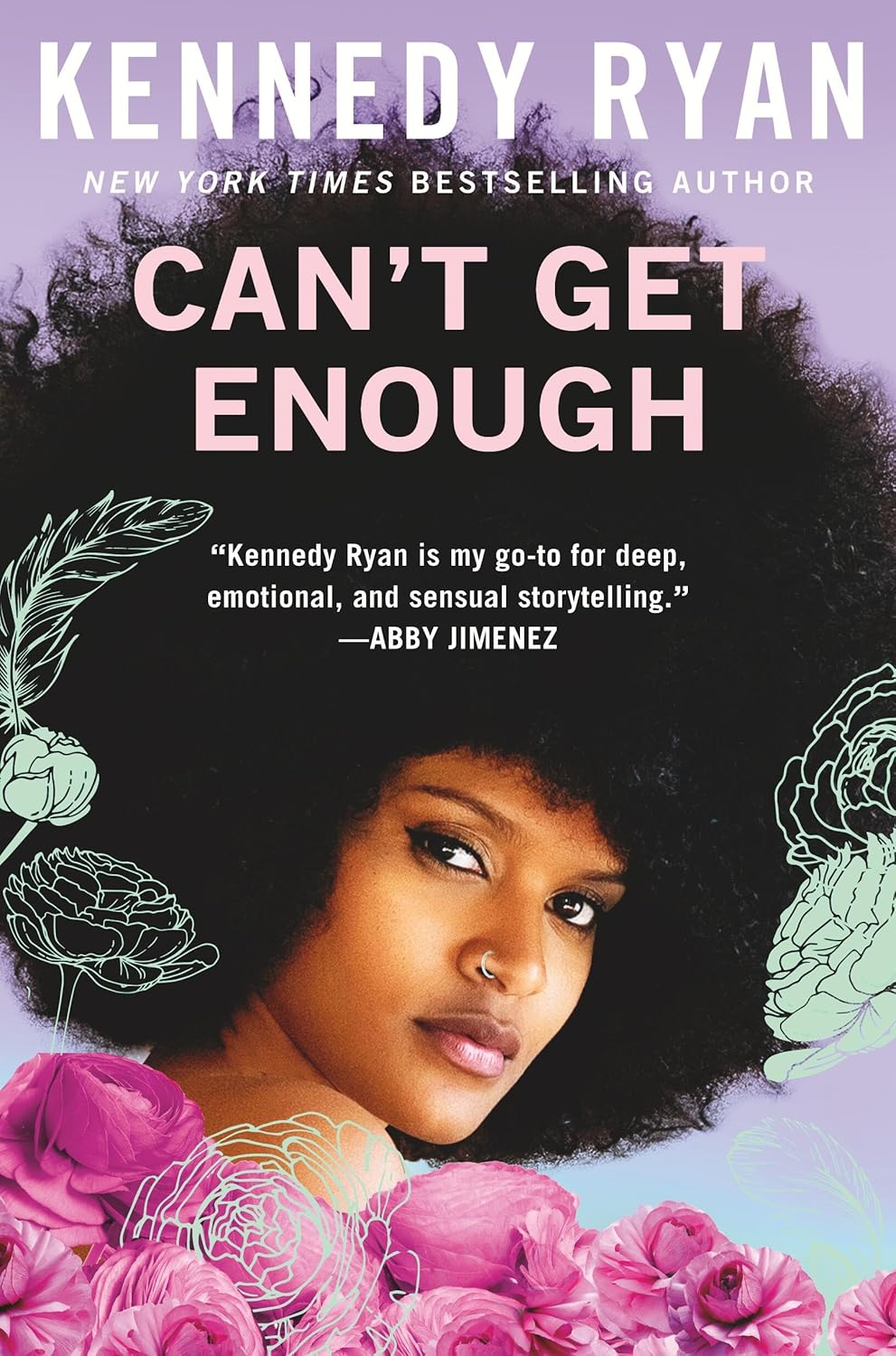

Can’t Get Enough (Skyland #3)

PROLOGUE

HENDRIX

T he front door stands wide open.

That has always meant a warm welcome at the two-story traditional house where I grew up, but now the sight makes me shiver more than the chilly wind of Christmas Eve whistling in my face.

“Is this it?” the Uber driver asks, watching me stand in the driveway with my rolling suitcase.

“Uh, yeah.” Uncertainty colors my voice and probably my expression if the driver’s Can I go now? face is anything to judge by. “This is it. Thanks.”

But is this home? The slightly overgrown lawn and uneven hedges would never have been tolerated by my mother in all the forty years of my life. The garage door is up and Mama’s pride and joy, Shortcake, her pearl-colored Lincoln MKC, is parked there. Mama wouldn’t leave her baby exposed like that.

Something’s wrong.

Something’s been wrong for a while. I haven’t exactly ignored it. I’m not one to bury my head in the sand, but I did hope it wasn’t as bad as I’d suspected. There are worse things to be guilty of than hope, but right now I can’t think of them.

As the Uber pulls off and I drag my bag up the driveway to the wide-open front door, the cloud of dread that has gathered in my belly for the last year calcifies and drops like a stone. I cross the threshold and shut the door behind me, surveying the front room Mama always kept immaculate. It was the first impression of our home, and I’ve never seen it in such disarray. Black dirt from an overturned plant soils the white carpet. A thin layer of dust dulls the end table’s usually shiny surface, and the lampshade is askew. The whole scene is askew, and I’m so disoriented it feels like I’m standing on the ceiling.

“Mama?”

Her name comes out thin and tentative, like when I called her as a child, scared there was a monster hiding under my bed. She always responded right away, coming into my room with a reassuring smile.

There is nothing reassuring about this answering silence.

Beep! Beep! Beep!

The smoke detector blares, breaking the quiet and jarring me from my stupor. White clouds billow into the hall, and I race to the kitchen. Plumes of smoke stream from a hissing pan on the stove. The acrid scent of something burning floods the air and stings my nose.

Shit!

Coughing, I rush past a mound of flour in the center of the kitchen floor, fumbling through the drawers where Mama always keeps dish towels. Wrapping one around the handle, I drag the pan away from the angry red burner. The pan sizzles when it hits the sink, a curtain of steam rising into the air and almost blurring—but not quite—the sight of raw chicken parts, chopped vegetables, half-formed piecrusts, and sloppily sliced fruit littering the counter.

What the…

Lifting the pan lid reveals collard greens, or what’s left of them. All the water boiled out and the charred mass is stuck to the bottom. I wrench open the oven door, and my nose wrinkles at the scorched, withered mess that may have been a ten-pound turkey in its previous life. Grabbing a second dish towel, I pull the smoking mess from the oven and plop it onto the range.

The smoke detector keeps squawking, so I stretch to vigorously wave my hands back and forth in front of the blinking alarm until it quiets. The silence that follows is even worse. With the immediate emergency of burning food addressed, I’m forced to deal with the bigger problem.

Where’s Mama?

“Ms. Catherine,” I say with sudden realization.

How many times has Mama walked over to our next-door neighbor’s house while her food simmered and baked? That has to be where she is. I sprint out the back door to the fence that divides our yards, pushing impatiently at the wobbly gate that is never locked between the two houses. I charge up the cobblestone path Mama’s closest friend laid through her garden, absently noting the frost-covered bushes sure to bloom in spring. I bang on the door.

“Ms. C,” I call, tugging on the metal handle. The door doesn’t budge. I go around front and ring the doorbell, but no one answers. Face pressed to the window, I’m disturbed by the quality of the darkened room I peer into. The stillness is stale like nothing has stirred in a long time inside.

“Hendrix? That you?”

I turn on the porch and frown at Mrs. Mayer, the neighbor from across the street Mama and Ms. Catherine never could tolerate.

“ Gossipy, is what she is ,” Mama used to say. “Couldn’t keep a secret if it was sewed in her jaws.”

“Mrs. Mayer.” I walk down the steps to meet her at the fence she’s peering over. “Have you seen Mama or Ms. Catherine?”

The papier-maché of her finely wrinkled skin creases with a series of emotions—surprise, dismay, sadness.

“I saw your mother earlier when I was out walking.” Meaning snooping. “But I haven’t seen her in a few hours. And Catherine, well…”

Her eyes drop to the grass and then lift, surprising me with their wetness.

“Well, Catherine passed. We buried her two weeks ago. You didn’t know?”

My head spins and my fingers shake as I grip the fence for support.

“What do you mean…” I grapple for words, but can’t form a coherent thought. It’s not possible my mother’s best friend died two weeks ago and I didn’t know. “She… died? How?”

“Heart attack.” Mrs. Mayer shakes her head, letting her gaze drift over to Ms. Catherine’s front porch. “Your mama didn’t take it well, as I’m sure you can imagine.”

I’ve been out of the country for work, but Mama and I spoke several times over the last few weeks, and most of those times she seemed lucid and pretty close to her usual self. In none of those conversations did Ms. Catherine’s death come up. We talked yesterday to confirm my flight time. I make sure to come home at least once a month, twice if I can, but work has slammed me hard recently. I called Ms. Catherine a couple of times last week and got voice mail, but that has happened before. She always calls back.

Not this time.

“I can’t believe Betty didn’t tell you,” Mrs. Mayer says, her look shifting from mournful to speculative. “I wondered why you weren’t at the funeral.”

“I… yeah, I…” There’s no answer for it. I refuse to give this woman more information that’s none of her business.

“So is Betty missing?” Her gaze sharpens, snaps to our back door, which, in my haste, I left open. A few tendrils of smoke straggle from the kitchen into the early evening air.

“No, not missing. Not home. I just got in from Atlanta and wondered if you’d seen her. I’m sure she’s out running some last-minute errands or something.”

“But her car’s in the garage,” Mrs. Mayer states. “She wouldn’t walk to the grocery store.”

“I need to go, Mrs. Mayer.” I turn abruptly and don’t wait for her to acknowledge the dismissal. “Merry Christmas.”

“Let me know when you find her,” she calls.

My steps stutter at the word “find,” but I speed-walk back into our house.

Mama’s missing.

When we first got the Alzheimer’s diagnosis, of course the doctors told us wandering was a possibility, but it’s not something we’ve had to deal with much before. Not like this. I need to call the police. I have no idea how long she’s been gone, where she might be. I knew the situation here wasn’t sustainable. It was patched and Band-Aided until we could figure out a long-term solution, and Ms. Catherine was the glue barely holding it all together. But she’s gone now, and Mama’s missing. An icy rivulet of fear runs down my spine, and I’m paralyzed. I—who always know what to do, where to go, what the next step should be—stand frozen in place with a sinking sense of dread and awful knowing. My throat closes around a sob, choking it into a whimper. I blink at the tears gathering in my eyes and swipe them.

“Get your shit together.” I pull the phone from my pocket, poised to dial the police department, but it rings before I can initiate the call.

“Hello?” I say it like a question because everything is right now. I know nothing except the terror rolling through my body like a giant snowball hurtling toward a cliff’s edge.

“Ms. Barry?” It’s an even voice—starched, calm. “Hendrix Barry?”

“Yeah… um, yes. I’m Hendrix Barry.”

“I’m Officer Billings. We have your mother here.”

His words loosen the fist in my chest. My heart is a raging rhythm in my rib cage. The blood rushes to my head and I draw a shaky breath. I shuffle through the heap of flour to slump against the counter in relief, heedless of the white powder dusting the black boots I thought I couldn’t live without last week.

“Is she hurt?” My voice cracks under the strain.

“She’s fine,” Officer Billings replies, his tone professional, but not unkind. “A little… confused, but doesn’t seem to be worse for wear. Your information was in her purse and written on her hand.”

“Where is she?” I grab Mama’s car keys from the hook on the wall by the fridge, already on my way to the garage. “At the police station?”

“No. We’re at an old plaza off Plymouth Ave.”

“The one where the Dollar General used to be?” I frown, starting the car and peeling out of the driveway like I’m being chased by goblins.

“Yeah, that’s the one. Security guard saw her wandering around the parking lot. The address—”

“I know where it is.” I change lanes, barely checking for oncoming traffic. “I’m only about five minutes away. Can you—”

“We’ll be here until you arrive.”

“Thank you.”

I barrel through a yellow light, glad that most people on this side of town seem to be off the streets this late on Christmas Eve. Tears track a hot streak over my cool cheeks.

“Stop,” I snap, swiping impatiently at the wetness. “Mama will be upset enough without seeing you all broke down.”

But broke down is exactly how I feel, like every wall, every thing that has been holding me up, holding my fears back, collapsed when I saw the chaos at the house.

I pull into the parking lot and it’s like stepping back in time, except years ago this plaza was the thriving center of our community. I’d be here with Mama all day on Saturdays, roaming from Cato to Lee’s BBQ to the small bookstore at the end of the row whenever I wasn’t helping in her bakery, Sweet Tooth. The pastel cupcake sign that used to grace Mama’s shop is long gone. A hardware store took over when she had to shut down, but even that store has left the plaza. The sign hanging up now says FOR LEASE . A haze of disuse shrouds the lonely plaza. Even the few vehicles in the parking lot seem not so much parked as put out to pasture.

I spot the squad car right away and pull up beside it. Not even bothering to turn off Mama’s car, I slam into park and jump out, leaving the driver’s door open. The police officer leans against the car, but I glimpse Mama in the back seat and my heart clenches. Once when I was sixteen, the cops picked up some of my friends and me for “cruising.” Whatever we were doing was harmless, but we were a bunch of Black kids hanging out late, so we must have been up to no good. They made me sit in the police car until Mama came, and I quaked in fear waiting for her to arrive. All my adolescent bravado fell away and I remember feeling so young and so small in that big back seat. It’s Mama in the back of the cop car now, but I still feel small and completely unprepared for what’s ahead.

It’s funny how the tables turn.

I’m only now realizing that often when people say “it’s funny,” they really mean that it’s… sad. A sad reversal of fortune. To have always been the parent. And now to be…

Mama doesn’t look up, but I sense that she knows I’m here. I reach for the door handle, but the officer stays my hand.

“Can we talk for a minute before you…” He tips his head toward the car.

I lick my lips nervously at the ominous weight of his words. “Of course.”

“This was in her purse.” He extends a slip of paper to me.

If lost, call my daughter Hendrix Barry.

My cell number is scribbled at the bottom.

If lost , as if she’s a misplaced item. Something that could be easily returned, only I don’t think anything can bring my mother back. Not ever really again.

“That’s how we found you so fast,” the officer continues. “I checked the records, though, and we’ve, uh… had a few calls about her before. She seems a little more disoriented this time. In the past, we called a Catherine Simmons.”

“Yeah, she… um, Mrs. Simmons very recently passed away. I didn’t find out until tonight.”

“What’s your mother’s condition?” he asks, eyes trained on my face.

“Alzheimer’s.” The word still feels unfamiliar, the hard consonants of it scraping against my teeth and tongue. “She was diagnosed last year. Early stage and it’s been manageable. I live in Atlanta, but she didn’t want to move there. She wanted… she wants to stay here, to stay home. And we agreed only because she had Catherine.”

“Can I be frank?” Officer Billings asks, barely waiting for my nod before going on. “In cases like this, social services will step in and tell the family that if you don’t make some kind of arrangements, you’ll be held responsible if anything happens to her or to someone else.”

“Arrangements as in—”

“She can’t live alone anymore, Ms. Barry. What that looks like, you and your family will have to determine, but this can’t continue. Not just because it’s disruptive for us, but for her own safety.”

It’s nothing I didn’t know, but it’s a tidal wave, and the only thing standing between me and the inevitable crash was Ms. Catherine. Now she’s gone.

“This won’t happen again.” I flick a glance over his shoulder to my mother’s silhouette in the back seat. “We’ll figure it out. Thank you for calling and for taking care of her.”

He offers a brief nod and opens the door.

“Mama,” I say, smoothing the distress of the last hour from my tone. “Let’s go home.”

The eyes my mother lifts are familiar, because they are the same deep shade of sable brown I meet in the mirror every morning, but they are foreign in their vacant bewilderedness.

“Huh?” Mama says… asks.

“Let’s go home,” I repeat, taking her elbow gently, helping her out of the car.

I swallow a gasp at my first clear sight of her under the parking lot lights. Her hair is matted in places. Dark circles smudge under her eyes. She shivers, pulling a housecoat over the lounge pants I’ve never seen her wear beyond the privacy of our home. Her tennis shoes are mismatched.

And she smells.

That is maybe the most heartbreaking detail of this scenario. My mother, who has always showered morning and night, smells like she hasn’t showered in days.

“Come on, Mama,” I say, taking her elbow and guiding her to the passenger seat. I go to fasten her seat belt, but she knocks my hand away.

“Hendrix Rae,” she snaps, her voice low and indignant, defiant. “I’m not a child.”

I much prefer her irritation, even her anger over the lost look in her eyes moments ago.

“Yes, ma’am. Sorry.” I climb behind the wheel and start the car, but don’t leave even once the officer does. I need to know. “Why’d you come here, Mama?”

She stares at the hands in her lap, blinking rapidly. “I… I got confused. I thought…”

Her lips clamp on whatever she was about to admit, and strain tightens the skin around her eyes.

“Your store, the bakery, used to be here.” I cast the statement like a hook, fishing for the answers that will make sense of this. “Can you please tell me why you came here, Mama?”

She squeezes her eyes shut and dips her head, shame in her trembling mouth and the tears like crystals on her bottom lashes. The silky belt of the robe is twisted into her clenched fist.

She can’t bring herself to admit it, but I know my mother came here tonight to open up her bakery, the one that’s been closed for more than a decade. It’s getting worse, and even being as involved as I have been and talking to her as regularly as I do, I didn’t know.

How could I not know?

After pulling Shortcake into the garage, I get out and head for the door to the house, but Mama stays in the front seat, her eyes trained ahead.

“Mama,” I say, stopping beside the passenger door and opening it. “You coming in?”

“No.” She wraps her arms around herself and shakes her head vigorously. “No, no, no. They’ll come back.”

“Mama, no one is there. No one is coming back.”

“They come at night sometimes.” Eyes wide and wild, she lowers her voice, casting a furtive glance at the front door. “They took my underwear, Rae. They go through my cabinets and refrigerator. They steal from me. I get scared.”

“No one’s gonna hurt you, Mama.” I swallow past the hot lump swelling in my throat. “I won’t let anyone hurt you ever. Okay?”

“You’re not here.” Her bottom lip quivers and she squeezes her eyes shut. “No one is here anymore. They’re all gone.”

Her mother. Her best friend. Her husband. All gone. One of the hardest parts of aging is being the one “still standing” when everyone else has found their peace lying down. And Mama has seen so many go.

Guilt washes through me, cresting in frustration and shame. I wasn’t here. I live hundreds of miles away.

“I’m here now,” I say, leaning against the open car door. “Come inside with me so we can eat Christmas dinner.”

What’s left of it.

She peers past me to the door, apprehension painting lines around her mouth and eyes. “You sure the coast is clear?”

“I’m sure.” I extend my hand to help her climb out of the SUV.

When we enter the kitchen, I stop short, shocked to see the flour swept up, the counters clear, a window open letting in cool fresh air to dispel the smoke. For a moment, I wonder if Mama’s delusion has some merit, when the kitchen door swings open.

“Aunt Geneva!” I press a hand to my racing heart. “I forgot you were coming.”

“That’s obvious,” grumbles my aunt, a retired elementary school teacher, walking over to the pantry and putting away the broom. “House wasn’t even locked up. Betty, you forget I was coming?”

Aunt Geneva, my mother’s older sister, wasn’t around very much when I was growing up. In their forties, they had a falling-out over land my great-aunt left them, one of those silly family spats that blows up and takes years to sort through. It’s only over the last ten or so years they’ve started truly repairing their relationship.

“I didn’t forget,” Mama says, her face held stiff. “How could I forget you were coming in from Virginia?”

Aunt Geneva’s sharp glance assesses Mama’s unkempt appearance, and then flicks to me. Our eyes hold, and the knowledge that Mama definitely forgot passes between us.

“Sissy,” Mama whispers, her voice shaking and a solitary tear streaking down her face. “I didn’t forget. I wouldn’t forget. How could I…”

Aunt Geneva crosses the kitchen in a few strides, pulling Mama close to her chest like the little sister she is in that moment, stroking her back and patting her hair.

“Of course you didn’t forget, Bet,” Aunt Geneva whispers. “And it don’t matter either way.”

She meets my eyes over Mama’s head and says, as much to me as to her, “’Cause I’m here now.”

Mama’s Christmas meal is obviously unsalvageable. While Aunt Geneva cooks breakfast for dinner—eggs, pancakes, grits, toast, hash browns, sausage, and bacon—I get Mama settled. First order of business is a shower. Then I do a quick wash and blow-dry for her hair, oiling her scalp and using the rollers she prefers. She’s been pretty quiet since we got home, as if she’s withdrawn into a safe place in her head; a quiet spot where no one expects her to remember or respond. Even still, I keep up a steady flow of one-sided conversation, every once in a while humming her favorite, “This Christmas.” Loves herself some Donny Hathaway.

“Y’all come on and eat,” Aunt Geneva calls up as I’m sliding the last roller into Mama’s hair. “’Fore this gets cold.”

At the table, we all punish our food—stabbing, jabbing, and pushing it around our plates in the stilted silence of the dining room. So different from the holidays of years past, where the laughter and Christmas music made it so you couldn’t hear yourself think, but that was fine because all you needed to do was laugh and eat. Mama picks at her eggs for a while and then, claiming fatigue, rises and slips off to her room. I’d usually try to coax her to stay, but I can practically see words burning a hole in the tip of Aunt Geneva’s tongue.

“We need to talk,” she says as soon as Mama’s footsteps on the stairs fade and her bedroom door snicks closed behind her.

“I know.” I raise a strip of bacon to my lips for a disinterested bite. “I didn’t find out about Ms. Catherine until today, that she had passed.”

“Me neither.” Aunt Geneva whooshes out a breath and shakes her head. “I even asked Betty last time we talked about Cat. She was vague. Didn’t sit right with my spirit, but I didn’t press. I should have pressed.”

I reach across the table and cover her hand with mine. “Don’t beat yourself up. We’ll both be more vigilant from now on. Apparently there have been a few incidents with the police department.”

I relay what the cop told me and the not-so-subtle warning about social services getting involved unless we address Mama’s living situation.

“A lot has to change,” I conclude. “She can’t go on like this.”

“You already know she ain’t leaving this house till she absolutely has to,” Aunt Geneva says, taking a sip of lemonade. “Took thirty years to pay off this mortgage. She’s lived here a long time. When you’re losing your memory, being in a place where your life happened, where the past is at your fingertips, is important. It’s reassuring.”

“You’re right.” I rub my temples, resignation like a vise around my head. “It’ll be hard to run my business from here. Everything’s based in Atlanta. Most of my clients are there, but I’ll figure it out.”

“No, ma’am.” Aunt Geneva’s gaze connects with mine across the table. Compassion swirls in the dark brown of her eyes. “You don’t have to uproot your life that way, Hendrix.”

“I have to be with her. She needs…” The enormity of the journey ahead, with its inevitable tragic end, overwhelms me. The pressure of maintaining my livelihood so I can afford to make sure Mama never wants for anything over the long haul comes crashing on me and steals my words. Fear and panic fist my heart until my breath comes short.

Aunt Geneva stands and comes around the table, taking the seat beside me that Mama vacated. She frames my face with her hands.

“Betty won’t leave yet,” she says, a determined glint in her eye. “And while she can still remember her life in this place, I don’t think she should, but I also don’t think you need to move home to this backwoods town.”

The sliver of humor in her voice soothes me long enough to return her small smirk.

“And she doesn’t want you to have to do that, Hen,” she says. “I’m an old woman, and them roots I got in Virginia ain’t doing a thing for me. I’ll move.”

“Aunt G, no. You—”

“ I am retired. Your cousin Ellie and the grands live in Costa Rica. They got the bar to run. Gerald and his family are stationed overseas. Till he’s out of the army, I don’t think they’ll be back stateside anytime soon. I only get to see my kids a few times a year as it is.”

“But your life is in Virginia Beach.”

“Girl, I’m seventy-seven years old. Husband passed. My kids ain’t around. I grew up here. Still got friends here. Shoot, New Hope Baptist was my church till I married and moved with your uncle Robert.” She chuckles and shakes her head. “They might not have even taken my name off the roll. I’ll be back on the usher board before you know it.”

“I can’t let you do that.”

“She’s my sister, Hendrix. My baby sister, and she needs me.” She leans forward to look in my eyes and taps the table with her index finger for emphasis. “There will come a time when your mama won’t be able to stay at home, but she’s still early in this. We gotta pace ourselves. Not just her, but you. Things will get worse, and we’ll face another set of decisions. Harder decisions, but we’re not there yet. I think you can stay in Atlanta, run your business and your life without much disruption, and come home every chance you get.”

The idea floats through the chaos of my thoughts, taking a few seconds to settle. Aunt Geneva’s plan will require many adjustments in how I run the business, how I run my life, but not as much as having to be here all the time would. It may be a temporary compromise we can all live with. It’s probably the best we can do for now, but guilt still gnaws at my insides.

“Don’t let that guilt eat you alive,” Aunt Geneva says.

I stare at her, amazed how she and Mama sometimes seem to pluck the thoughts right out of my head.

“How do y’all do that?” I chuckle. “I couldn’t get away with nothing growing up because seemed like Mama was always two steps ahead of every lie I tried to tell.”

“We got discernment,” Aunt Geneva replies with a wink and a smug smile. “God gon’ always tell on you.”

We both laugh at that, though I’m not sure she’s joking. If there’s one thing Mama and Aunt Geneva have always taken seriously, it’s church.

“Are you sure?” I ask, the flash of humor squashed by the returning weight of worry.

“There is very little I’ve been sure of since Betty was diagnosed,” Aunt Geneva says, blinking away tears. “But coming to live with my sister and taking care of her as long as I can—I never been more sure of anything in my life.”

She pulls me close and tucks my face into the curve of her neck. My tears soak her shirt like I’m a child again. I can’t help but think of Mama tonight, the small figure in the back seat of that police car.

It’s funny how the tables turn.

Right now, I wish I could go back to being that child who counted on Mama and Daddy for everything. So far from the woman I’ve become who runs the world around her with a steady hand. I’m barely standing on wobbly legs and with a trembling heart, but I cannot afford to fail and I won’t let her down.

The tables have turned, and now Mama’s the one counting on me.